영화는 문화의 경계를 넘어 사람들을 하나로 연결하는 힘을 지녔다고 종종 낙관적으로 이야기된다. 하지만 이러한 관점은 보통 두 가지 범주에만 국한되기 쉽다. 하나는 가족이나 연애 등 보편적인 주제를 다룬 감성적인 드라마, 다른 하나는 상업적 성공으로 세계적인 인기를 끈 흥행작이다.

그렇기에, 보다 복잡한 사회•계급적 문제를 지속적으로 탐구하면서도 이를 초국가적인 공감대로 끌어올리는 감독은 드물다. 봉준호 감독은 그중 한 명이다. 그는 경제적 불평등, 사회적 불안, 환경 위기, 정부 비판, 사회의 무기력 등을 장르영화의 틀 안에서 다루며, 때로는 어둡고 유머러스하게 때로는 불편하고 충격적으로 풀어낸다.

초기에는 비교적 적은 예산의 한국영화 네 편으로 커리어를 시작했지만, 지난 10여 년간 제작한 영어권 영화 세 편과 함께 그의 명성은 전 세계적으로 급상승했다. 특히 2019년작 <기생충>은 각종 상을 휩쓸며 그의 커리어 사상 최고의 흥행작이 되었고, 전 세계 극장에서 2억 5800만 달러 이상의 수익을 올렸다.

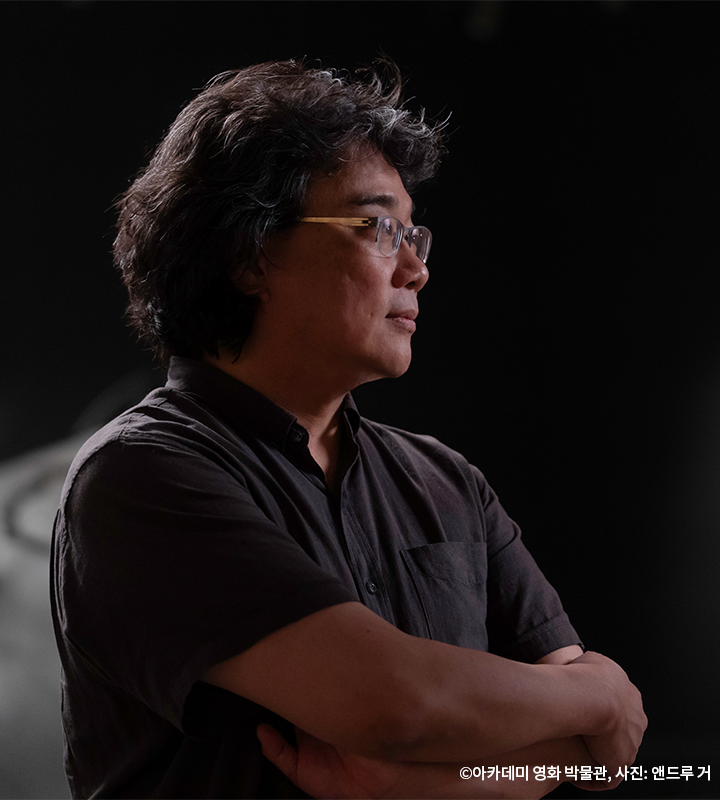

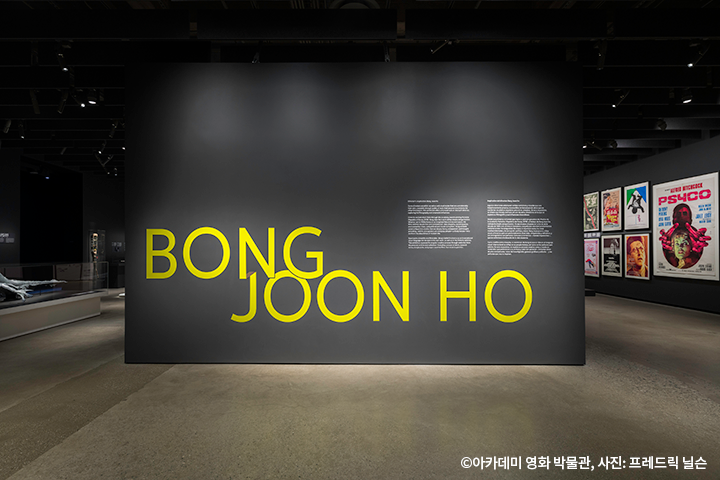

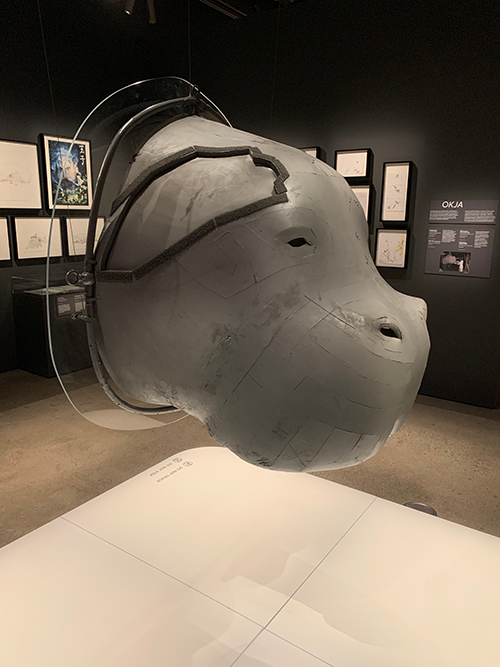

이처럼 여전히 진행 중인 봉준호 감독의 인상적인 커리어는 로스앤젤레스(LA)에 위치한 아카데미 영화 박물관(Academy Museum of Motion Pictures)에서 열리는 특별 전시 <Director’s Inspiration: Bong Joon Ho >를 통해 기념된다. 이 전시는 그의 작품뿐만 아니라 창작 과정, 그리고 영향을 받은 영화들까지 조명하는 최초의 단독 전시로, 대부분 봉준호 감독의 개인 아카이브에서 가져온 100여 점 이상의 오브제로 구성되어 있다. 여기에는 <기생충>의 상징적 수석과 가족 사진, <괴물>의 생물 모형, <옥자>의 돼지 캐릭터 머리, <설국열차>의 소품 총알과 군사 메달 등이 포함된다.

전시는 2027년 1월 10일까지 이어지며, 개막 후 3주 동안 박물관의 최첨단 상영관에서는 봉준호 감독의 작품을 조명하는 특별 회고전이 열렸다. 여기에는 봉 감독이 개인적으로 좋아하는 영화들도 함께 소개되었는데, 특히 <더 씽(The Thing, 1982)>의 4K 복원판 상영 후엔 존 카펜터 감독이 직접 참석해 봉 감독과 함께 관객과의 대화를 진행했다. 이 자리에서 봉 감독은 곧 제작할 예정인 차기 공포영화의 음악 작업을 77세의 거장 카펜터 감독에게 부탁했고, 두 사람은 이를 악수로 흔쾌히 약속했다.

<Director’s Inspiration: Bong Joon Ho >는 그의 작품뿐만 아니라 창작 과정, 그리고 영향을 받은 영화들까지 조명하는 최초의 단독 전시다

<기생충>의 가족 사진

봉준호 아카이브의 에너지

아카데미 영화 박물관은 LA라는 미국 영화 산업의 중심지에 위치하고 있지만, 2021년 개관 이래로 다양한 배경과 국적을 지닌 영화인들을 조명하는 데 집중해 왔다. ‘Director’s Inspiration’ 시리즈는 이러한 철학을 직접적으로 반영하며, 지금까지는 미국의 스파이크 리 감독, 프랑스의 아녜스 바르다 감독이 소개된 바 있다. 박물관은 감독의 명성과 업적뿐 아니라, 독창적인 방식으로 예술적 영감을 해석하고 새로운 서사를 개척해 후배 영화인들에게 영향을 미친 인물을 선정한다.

전시 큐레이터 미셸 푸에츠(Michelle Puetz)는 봉준호 감독이야말로 이 모든 기준을 충족하는 인물이라며, “그의 세계적 영향력은 두말할 필요도 없습니다. <기생충>으로 아카데미 4관왕을 수상하면서 아카데미와도 특별한 인연을 맺었죠. 하지만 이번 전시의 핵심은 대중에게 익숙한 <기생충>을 넘어서, 그의 초기 작업과 성장 배경, 그리고 어떻게 아카데미 수상 감독이 되었는지를 심층적으로 조명하는 데 있습니다”라고 밝혔다.

봉준호 감독의 적절성과 상징성은 소셜네트워크서비스(SNS)에서도 확인할 수 있다. 2019년 10월, 마틴 스코세이지 감독이 마블 영화를 “놀이공원 같다”며 “진짜 영화가 아니다”라고 발언한 후, “이게 바로 영화다(This is cinema)”라는 밈이 유행했다. 이후 2021년 5월 봉 감독이 “저에게 그게 바로 영화입니다(To me, that’s cinema)”라고 말한 영상이 확산되며, 이 표현은 새롭게 재해석되어 큰 호응을 얻었다. 이는 영화 팬뿐만 아니라 일반 대중에게도 봉 감독을 “영화 그 자체”로 상징하게 한 계기가 되었다.

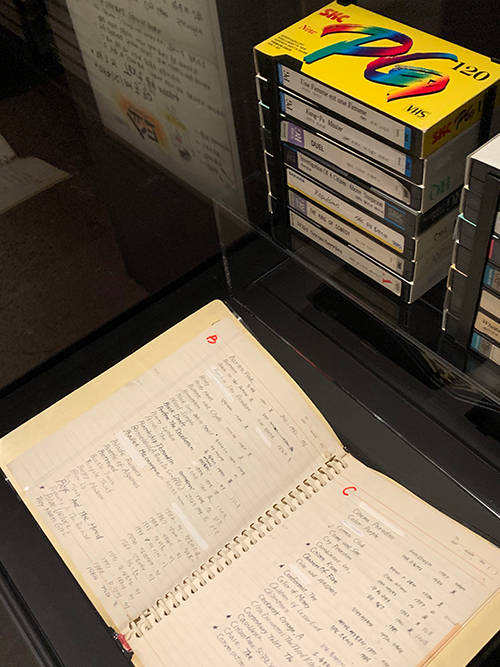

이번 전시는 약 2년 전부터 기획되었으며, 푸에츠 큐레이터는 서울을 두 차례 방문해 봉준호 감독을 직접 만났다. 그의 작업실은 창의적인 에너지로 가득했고, 벽면에는 현재 작업 중인 애니메이션 <더 밸리(The Valley)>의 스토리보드가 가득했다. 봉 감독은 오래된 노트, 각본 초안, 리서치 자료, 소중한 영화 소품, 책, VHS, CD, DVD 등을 한자리에 모아 관리하고 있었다. 푸에츠 큐레이터는 “그는 거의 자신의 아카이브 관리자 같아요”라며 놀라움을 드러냈다.

봉준호 감독의 창작 기록과 아카이브 정신을 고스란히 보여주는 전시

정확성과 몰입의 집념

관람객과 기자들의 반응 역시 매우 긍정적이다. 전시가 특히 매력적인 이유는, 전시품들이 매우 개인적이고 사적인 성격을 띤다는 점이다. 네바다에서 온 관람객 마커스 애시우드와 그의 아내는 “<기생충>을 보고 큰 감명을 받아 다른 작품도 알고 싶어서 왔어요”라고 말했다. 또 다른 관람객은 “그가 어린 시절 TV로 미국이나 유럽의 영화들을 보며 얼마나 분석적으로 받아들였는지를 보고 놀랐어요. 예술이 이렇게 깊이 각인될 수도 있구나 싶더라고요”라고 전했다.

이번 전시는 봉준호 감독의 정신세계를 깊이 있고 폭넓게 보여준다. 어린 시절 그가 직접 그린 만화와 스케치는 정치적 이슈와 사회 변화, 주변 일상 문제에 대한 그의 관심을 보여주며, 데뷔작 <플란다스의 개>의 리서치 노트에서는 관찰력과 인물에 대한 비판 없는 시선이 엿보인다.

봉준호 감독이 얼마나 치밀한 플래너인지도 전시의 주요 포인트다. 많은 감독들이 스토리보드를 사용하지만, 봉 감독의 스케치는 초기 단계부터 놀라운 디테일을 담고 있다. 그는 연세대 재학 시절 학보에 만화를 연재하기도 했으며, 이는 훗날 영화의 샷 앵글이나 배우에게 요구하는 리액션까지 시각적으로 전달하는 데 큰 도움이 되었다. 푸에츠 큐레이터는 이렇게 덧붙였다. “그는 영화 작업에 몰입하면 그 세계에 완전히 들어갑니다. 스토리보드를 여러 번 수정하고, 대본 뒷면에 직접 그림을 그리며 장면을 반복해서 다듬죠. 그건 단순한 집착이 아니라, 정확성과 몰입에 대한 집념이에요.”

또 한 가지 인상적인 부분은, 그가 젊은 시절부터 자신의 감정 반응을 분석하고 이해하려 노력했다는 점이다. 군 복무 후 그는 ‘노란문 영화 동아리’를 만들어 서울 일대 대학생들과 함께 영화 감상과 제작 활동을 했다. 당시 한국에서는 해외 영화에 접근하기 어려웠기에, 그들은 VHS 복사본을 돌려 보며 연구했다. 봉 감독은 그 복사본 대여 담당이었다.

그의 노트에는 <파고> <양들의 침묵> 등 영화의 카메라 앵글과 블로킹 분석 흔적이 남아 있다. 그는 이러한 분석을 통해 자신의 감정 반응을 이해하고, 이를 바탕으로 자신의 영화에 적용해 갔다.

‘노란문 영화 동아리’를 만들어 서울 일대 대학생들과 함께 영화 감상과 제작 활동을 했던 봉준호 감독.

영화적 뿌리와 시네필 시절의 흔적을 보여주는 상징적인 사진이다

봉준호만의 언어로

전시는 대체로 연대기 순으로 구성되어 있으며, 여덟 편의 장편영화에 대한 스토리보드, 대본, 리서치 노트가 주요 소품과 함께 전시되어 있다. 한쪽에는 단편영화 영상이 상영되는 어두운 방이 마련되어 있고, 그 옆에는 그에게 영향을 준 20편의 영화 포스터가 언어별로 전시되어 있다. 알프레드 히치콕의 <싸이코> 포스터도 그의 개인 소장품 중 하나다.

<옥자>의 돼지 머리 인형이 특히 눈에 띈다. 디지털로 제작된 캐릭터지만, 실제 촬영 현장에서 배우들이 상호작용할 수 있도록 만든 실물 모형이다. “그는 컴퓨터그래픽(CG) 환경에서도 인간 간의 교감을 중요하게 여겼어요. 이 인형은 그런 인간애의 상징이에요.”

전시의 하이라이트는 스토리보드로 가득 찬 방이다. 세 벽면을 둘러싼 스토리보드 사이에는 주요 소품들(<기생충>의 수석, 한국어 해적판 영화 교재 등)이 전시되어 있고, 실제 촬영 장면과 스케치를 비교한 영상도 상영된다. 중앙에는 봉 감독이 실제 사용하는 작업 테이블이 놓여 있는데, 이 테이블은 <설국열차>에서 소품으로도 사용된 바 있다. 푸에츠 큐레이터는 “과거의 도구가 미래를 창조하는 공간이 된다는 점에서 상징적이다”라고 설명했다.

결국 이번 전시는 단순한 영화 기념품 전시가 아니라, 한 젊은 예술가가 무엇에 열정을 가졌고, 그것을 어떻게 분석하고, 자기만의 언어로 승화시켰는지를 보여주는 여정이다. 푸에츠 큐레이터의 말처럼. “이 전시는 제게 매우 감동적이었어요. 팬으로 시작했지만, 이제는 전혀 다른 시선으로 그를 바라보게 되었어요. 그는 약자를 비추는 사람입니다. 그가 그리는 인물들은 전형적인 영웅상은 아니지만, 불공정한 사회 구조 속에서 싸워 가는 인물들이죠. 그것이야말로 이 시대와 가장 깊이 공명하는 지점이라고 생각합니다.”

브렌트 사이먼이 직접 촬영한 <옥자>의 돼지 머리 인형

봉준호 감독에게 영향을 준 20편의 영화 포스터들

봉준호 감독 영화의 스토리보드들로 가득 찬 공간

봉준호

BongJoonHo

아카데미영화박물관

AcademyMuseum

아카데미특별전

전시추천

GLOBAL

A Passion Resonating

with the Times

Academy Museum

of Motion Pictures

Celebrates Bong Joon Ho With Special Exhibition

Words by Brent Simon

(Film Critic)

Photo by Andrew Ge and

Fredrik Nilsen

2025-04-16

The universality of cinema is frequently discussed, in optimistic terms, as a way to bridge cultures and help bring people together. Often, though, that saying is only viewed through one of two lenses — that of highly sentimental dramas rooted in family or romantic problems that have a common relatability, or that of purely commercial success, a box office hit in one country or region that enjoys a sometimes unexpected breakthrough in other territories.

It’s rare, the number of filmmakers of truly international consequence whose work consistently incorporates and addresses more complex social and class themes that in and of themselves transcend national borders. Bong Joon Ho is one such director — funneling unique portraits of economic inequality, societal and environmental anxiety, governmental critique and social malaise through genre lenses that are often darkly humorous, but just as frequently unsettling.

After a quartet of fairly modestly budgeted and very well received domestically produced films to begin his career, he has, over the last decade-plus, vastly expanded his profile with three films told largely in English and another, 2019’s Parasite, that became both an awards juggernaut and far and away Bong’s highest-grossing movie, making over $258 million in theaters.

The arc of this impressive career, still very much in bloom, receives a loving tribute at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles with the new, recently opened exhibition Director’s Inspiration: Bong Joon Ho, which highlights not just the 55-year-old director’s celebrated filmography, but also his creative process and cinematic influences. The first exhibit wholly dedicated to Bong’s work, the collection features more than 100 objects, most sourced from Bong’s personal archives. Among some of the most recognizable pieces on display are Parasite’s suseok rock (or scholar’s stone) and family portrait, an unnerving creature model from The Host, the so-called “stuffy” puppet head of the giant pig title character in Okja, and prop bullets and military medals from Snowpiercer.

In parallel with the showcase, which is scheduled to run through January 10, 2027, a special retrospective of Bong’s films screened in the venue’s state-of-the-art theaters during the first three weeks of the exhibition’s booking. Sprinkled into this mix as well were a couple of his personal favorites, like a 4k restoration of The Thing, where Bong appeared in person alongside director John Carpenter at a post-screening Q&A and made a handshake deal with the 77-year-old legend for Carpenter to provide the score for a horror film Bong is planning to soon make.

<Director’s Inspiration: Bong Joon Ho > is the first solo exhibition to spotlight not only his films, but also his creative process and the movies that influenced him

The family portrait from Parasite

The Energy of Bong Joon-ho's Archive

Although it’s housed in Los Angeles, the inarguable capital of the American film industry, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has, ever since its 2021 opening, been dedicated to showcasing filmmakers from a broad kind of spectrum of backgrounds and nationalities. Its Director’s Inspiration series represents a clear extension of that overarching philosophy, with its two previous celebrants being American-born director Spike Lee and French director, photographer and multimedia artist Agnes Varda. While renown and distinction are of value in choosing subjects, the museum is also invested in focusing attention on film artisans who have synthesized their own antecedent inspirations while staking out bold new narrative terrain, and who have made a profound impact on other filmmakers and young artists.

For Michelle Puetz, Exhibitions Curator at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, Bong checked all of those boxes, and thus made perfect sense as the third selection in the Director’s Inspiration series. “I feel like his global importance and significance is certainly undeniable,” she said. “He has a special relationship to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences because of the historic, significant multiple wins with Parasite in 2019. But with the series, what I really think is important for us to do as an institution is to represent him beyond the film that many of the public may know him for, and to look at all of the films that came before, to look at early career materials and to contextualize how he got to be the Oscar-winning filmmaker that he is today.”

The suitability of Bong’s selection is further affirmed with a quick glance on social media on virtually any day. In October 2019, Martin Scorsese first made remarks comparing Marvel movies to theme park rides, and saying that they were “not cinema.” This sparked a firestorm and provoked much online debate, both amongst hardcore cinephiles and those with less strongly held opinions. Rather quickly, memes developed using the quote “This is cinema.” Sometimes this was meant as a form of ironic response, but just as often it was used as a shorthand way to celebrate the piercing beauty or moving artfulness of some piece of short-form video.

A funny thing then happened, though. A clip and screenshot of a May 2021 interview with Bong, in which the filmmaker says, “To me, that’s cinema,” was seized upon by cinephiles and then younger members of the broader public — far eclipsing all memes using the original Scorsese quote. Bong’s rhapsodic rumination and quote became an enormous viral sensation in its own right, even amongst people who might have only ever otherwise glimpsed him onstage at the 92nd Academy Awards, if at all. Bong, not unlike Quentin Tarantino, is a director who utterly lives and breathes movies. Him becoming visually synonymous with cinema for millions of only casual movie-watchers is a wonderfully delightful development.

Planning on the Director’s Inspiration exhibition started almost two years ago, not long after Puetz arrived at the museum. She traveled to Seoul twice to meet with Bong, and described his office space as a lively hive, buzzing with creative energy. Storyboards from The Valley, the animation project that he’s currently working on, line the walls, while beloved novels, VHS tapes, DVDs and CDs share space alongside old notebooks, research materials, drafts of shooting scripts and keepsake film props. “He’s his own personal archivist, in a way,” said Puetz, who saw in these items the chance to tell a compelling story about Bong.

An exhibition that captures

Bong Joon Ho’s creative journey and meticulous archival spirit

A Commitment to Accuracy and Immersion

The reaction from reporters to the exhibition has been largely positive, with many citing exactly this quality — the highly personal nature of its display items — as being the main attraction. The reception from a cross section of museum visitors on a balmy weekday visit by this author also highlighted the exhibition’s ability to connect across a variety of demographics, with one person even referencing the online meme above.

Several people interviewed were certainly avowed Bong enthusiasts, having seen three or more of his eight films. But a handful of out-of-town visitors had seen only Parasite, and were drawn into the exhibit by the promise of learning more about the life and other work of this curious filmmaker who they had watched score four Academy Award victories, including Best Picture and Best Director, for that film. “We saw Parasite and loved it,” said Marcus Ashwood, a postal worker from Nevada visiting with his wife Jenny. “So we wanted to come and see all about his other movies too. Now we’ll kind of know some of the backstories of what inspired him to make his other movies, if or when we watch those.”

Still other attendees were pulled into a visit by a friend or spouse, unfamiliar with Bong’s movies but open to exploring his work. “I think it’s interesting and pretty wild that he was influenced by so many American and even European movies that he saw on television when he was young, and absorbed them in such an analytical way,” said Taylor Mustow, an accounting supervisor from neighboring Orange County. “I guess it shows how deeply different art can really imprint on you when you’re open to and excited by it.”

Indeed, the exhibition feels like it serves as a revealing glimpse into Bong’s psyche, in ways both general and incredibly specific. Sketches and cartoons from his youth indicate a man very much plugged into and grappling with the political issues, societal shifts and everyday struggles he saw around him growing up. A research notebook from Bong’s debut feature Barking Dogs Never Bite, which featured some characters and details based on his own life, confirms his keen eye for detail, and refusal to judge his characters.

One of the biggest takeaways is just how meticulous of a planner Bong is. While many, many filmmakers utilize storyboards, Bong’s drawings often show an atypical level of detail, even at their earliest stages. Comic books were an early passion, and while enrolled at Yonsei University, he published a recurring cartoon strip in the school newspaper. That experience seems to help Bong not only plan shot angles but economically capture levels of specific reaction he can then communicate to actors during their performances.

“I have never had the experience of looking through someone’s materials, looking through notebooks, looking through storyboards, and then talking about revisions of storyboards — seeing how they go back, iterating a scene multiple times, seeing him sketching out storyboard revisions on the flip side of a script,” said Puetz. “This is someone who when he’s making a film is completely in that world and working with such dedication — he would say obsession — but with such precision and devotion to really getting things to be exactly the way he wants them to be.”

The other biggest illuminating element of the exhibition lies in discovering just how motivated Bong was in his younger years to understand his own emotional reactions to films. After a break serving his compulsory two-year military service, Bong returned to Yonsei in 1992, and co-founded the Yellow Door Film Club, which pulled together other film-loving students from nearby universities.

“It was a way for him and friends to get together and to both think about and analyze films, and then start working on shooting films together as a collective,” noted Puetz. “It was difficult to access films in Korea at that time, in the early 1990s, so they were circulated as VHS bootleg copies and Bong was in charge of that VHS lending library. We have a selection of those to really show the way in which he was starting to learn about and discuss film with other people, and the way film was circulated in an underground fashion through Korean cinephile culture at the time.”

Framed notebook entries illustrate the manner in which Bong studied and dissected the blocking and camera movements of films like Fargo and The Silence of the Lambs, breaking them down to their component parts. Years later, he would take inspiration from their stagings for his own impeccably composed shots. But this exhibition also make clear that his study then was also an inventorying of the emotional impact of various films upon him.

Director Bong Joon Ho founded the Yellow Door film club, where he watched and made films with fellow university students in Seoul. This photo symbolizes his roots in cinema and early years as a passionate cinephile.

In Bong Joon-ho's Own Language

Understanding that fact gives one a richer appreciation of Bong’s current-day methodical approach, and how and why he maps out both larger, complicated action set pieces as well as staged bits and pieces of visual humor. By stitching together moments small and large, Bong is able to help give his movies compellingly grounded emotional landscapes, and the feeling of a finely woven tapestry.

The exhibition is structured so that visitors can move almost chronologically through Bong’s professional canon, if they so desire. Various storyboards, shooting scripts and research notebooks for his eight feature films are accompanied by small props.

Off to the side, there’s a darkened room playing a video installation montage of Bong’s work, including some of his short films. At roughly 10 minutes, the non-sequential piece opens with Mother’s Kim Hye-ja dancing, and is edited together in an evocative, rhythmic fashion that indulges a couple match cuts (doorbells being rung in Parasite and Snowpiercer, for example), while mimicking both the commingled tone and elliptical editorial structure of many of Bong’s works.

Next to this room is a gallery of gorgeous posters in a couple different languages (including Bong’s own personal Psycho print) spotlighting 20 films, from Touch of Evil and Jaws to Barton Fink and Zodiac, that the director feels influenced him.

The large Okja puppet head, which Bong had created so that Ahn Seo-hyun’s Mija could interact with something physical on set, is quite striking. “It’s really a beautiful object, but I think it also represents the way in which, even when he’s working in a digital space with creatures that are created using CG, he’s thinking about the way people and humans interact, and about these connections that we make,” said Puetz. “There’s just a deep sense of humanity in all of his work, and it's a really beautiful representation of that.”

The beating heart of the exhibition, though, is a room lined with storyboards on three sides, and inset cubbyholes with key objects like the aforementioned suseok rock from Parasite, plus bootleg, Korean language copies of cinema texts from the 1990s. Prominently displayed in this room, under a side-by-side video presentation of schematics and the final, realized shots from several of Bong’s movies, sits a table that discerning film fans might find familiar. “That work table that he sat at when I first met him, where he does everything, it’s also a prop from Snowpiercer,” said Puetz. “So it’s like this beautiful metaphor of something from his past that he’s also creating the future on, as he does drawings for his new films.”

In the end, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures exhibition on Bong Joon Ho connects at an elevated level for cinephiles and still an interesting level for more casual moviegoers because it doesn’t present merely a collection of memorabilia. Rather, it shows the many influences and subsequent artistic progression of a young man — what first ignited his youthful passions, how he studied and dissected those inspirations, and then brought them to bear and incorporated them into his own work.

That’s rich and rewarding for anyone with avenues of creative expression in their own lives. But it’s also instructive just to see and think about as it relates to someone who grew up thousands of kilometers away from Los Angeles — how inspired he was by the universality in movies of other cultures, a universality now reflected back so deeply in his own work.

“I’ve never had an exhibition touch me so much personally,” admitted Puetz, when asked how her work on the exhibition impacted her perception of Bong. “I went into this a fan and I left with a different understanding of him and his creative genius. I see him as someone who recognizes and wants to celebrate the underdog. Like, (his characters) aren’t your conventional kinds of heroes. I think of them as unlikely heroes. But they are people who oftentimes face really difficult challenges in the midst of social structures and political structures that don’t necessarily support them, and I think there’s a profound resonance with that and our contemporary moment.”

Pig head prop from Okja, photographed by Brent Simon

Posters from 20 films

that influenced

director Bong Joon-ho

A space filled with storyboards from

Bong Joon Ho’s films